As a result of acquiring both the Synthesis Technology E370 and the Flame Instruments 4VOX, after also getting the Humble Audio Quad Operator and RYK Modular Algo earlier in the year, I’ve been stringing together a series of chord-based polyphonic patches using various forms of slow modulation to control the volume of each chord tone. From standard LFOs to chaos, and stochastic functions to ocean wave simulations, I’ve tried at least a dozen of this style of patching over the last several months. Some of these have used static chords that don’t really move anywhere. Different notes of a chord come in and out chaotically (in most cases), but the chord itself doesn’t change. Others are based on the harmonic series, where only one pitch change of the master oscillator affects all of the individual harmonics resulting in chord changes. All of those were composed using chaos or random as a pitch source. But, with one exception, it wasn’t until this patch that I used the NOH-Modular Pianist with real intent and composed a chord progression to move the piece along. To set a mood and provide some tension and relief with harmonic motion in addition to volume and timbre changes. And this time I went big with using all eight CV outputs, rather than just four.

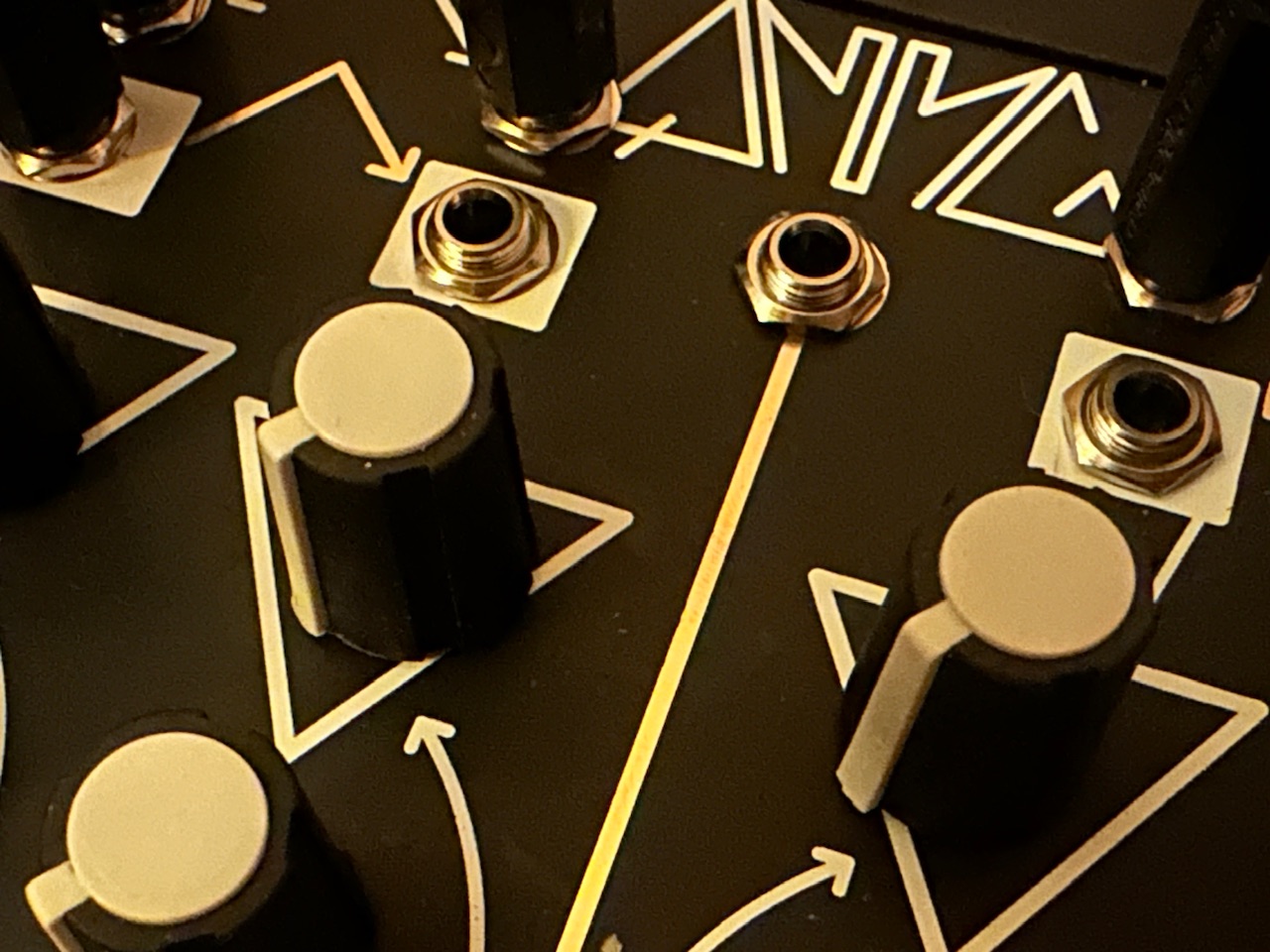

The NOH-Modular Pianist is an interesting module. It promises a world of harmonic movement in an environment where using chords isn’t a simple proposition. Polyphony in Eurorack is equipment and labor intensive. Each separate note of a chord requires its own separate oscillator, function generator, and VCA, at minimum. and requires its own discrete signal path. That’s a lot of patching for what is an easy task in a DAW or by using keyboard-based synths. It’s a lot of tuning (and re-tuning); lots of signals to tweak, and lots of modulation to account for. Before the Pianist, ways to get this sort of advanced polyphony was hard to come by. You could use a MIDI > CV converter, which has its own challenges, or else by painstakingly programming a pitch sequencer note by note, which requires a level of music theory knowledge that most don’t possess.1 MIDI > CV converters require careful calibration, and there are few sequencers with more than just four channels. But the Pianist is different.

Rather than programming chords note by note, Pianist uses standard western music shorthand for identifying chords, and the module does the rest. When you program it to play a CM7 chord, for instance, it knows to send out pitch data for C E G and Bb. It’ll even repeat chord notes in a different octave if no color tones are used. You can add two chord extensions beyond the 7th, called Colours in the Pianist, or use chord inversions to designate the third or fifth as the bass note in the chord. If a up to six note chord can be played on a piano, it can be played by the Pianist.

Users can freely enter chords from scratch in Free mode, or, to make the job even easier, set it to Scale mode and choose only from chords within your chosen key. The scale can be set to Major, Minor, or any of the modes2 and Pianist does the rest. So, for example, if a user in Scale mode were choose A Major as the scale, Pianist would present you with only AMaj, Bmin, C#min, DMaj, EMaj, F#min, G#dim, the diatonic chords in A Major, in order to facilitate easier chord progressions for theory novices. As long as your oscillators are tuned, your chords will be in key. Nifty. For those who want to use chords outside of a key, or if your composition isn’t really in a specific key, Free mode allows for creating chords from scratch. Virtually any chord is possible (up to six notes). In both modes, harmonic complexity is simple, with up to two color tones available, and made even simpler in Random Gate mode where each gate received will add random colors automatically, and choose colors that make harmonic sense within that chord. The workflow in creating chord progressions is intuitive. I was quickly making fairly complex progressions with repeats and skipped chords with ease.

Though Pianist is a boon to those of us seeking access to polyphonic 12TET harmonic movement in our Eurorack patches, it does have its weaknesses. Though you can move notes up and down in octaves to create chord depth, it’s done in a haphazard way. Rather than setting each note for the exact voicing you’re looking for, you have to rely on functions Pianist calls Shift and Spread in order to get full, rich chords that don’t clutter a particular part of the audio spectrum, but it’s not exactly clear how that affects the chord as a whole. I can hear changes, but can’t always identify them. Easy variety, however, can be achieved when the Gate mode is set to Spread. No chord will be voiced exactly the same which creates intrigue.

The calibration for the module, at least in Version 1.0, is straight funky. This patch uses eight discrete oscillators. While tuning I sent a C from Pianist to set a baseline. But in order for the oscillators to play the C being sent, they each had to be tuned to G, which I found odd. The newest firmware, 1.2, addresses tuning and scales in a way that version 1.0 does not, which is a great improvement by all accounts, even if I haven’t used it yet to note any changes. Since I’m using Pianist in Free mode in this patch, however, there wasn’t a compelling reason for me to upgrade, though I certainly will now that I’ve finished recording it, even if I have an aversion to the upgrade processes of most digital modules.

The screen has a lot of information, and not a lot of room. However, navigation is still reasonably simple and the information on the screen laid out such that it’s not hard to read. It’s easier to read and use than many far more established modules like the Disting Ex, Kermit Mk3, or uO_C, even if there isn’t a lot of screen real estate. The interface is super easy to navigate using the mini joystick/push button. Version 1.2 is reported to have an even more streamlined navigation and menu system. Though altering global settings like the Scale, Gate or Spread behavior requires some menu diving which is never fun, programming chords decidedly does not. It’s a point and click operation made easy with the joystick, all done on one level. Move the cursor to what you want to change, click, move the joystick to the desired value, and click. Done.

A major issue with version 1.0, which may have been changed, is that it always boots up with the first saved sequence. Unless you save your progression to one of the user slots, you will lose your work if the module power cycles. If you don’t have much in your progression, or it’s a super simple that’s no problem. But if it’s long or has a lot of direction you might be losing a lot. Ask me how I know. 😕

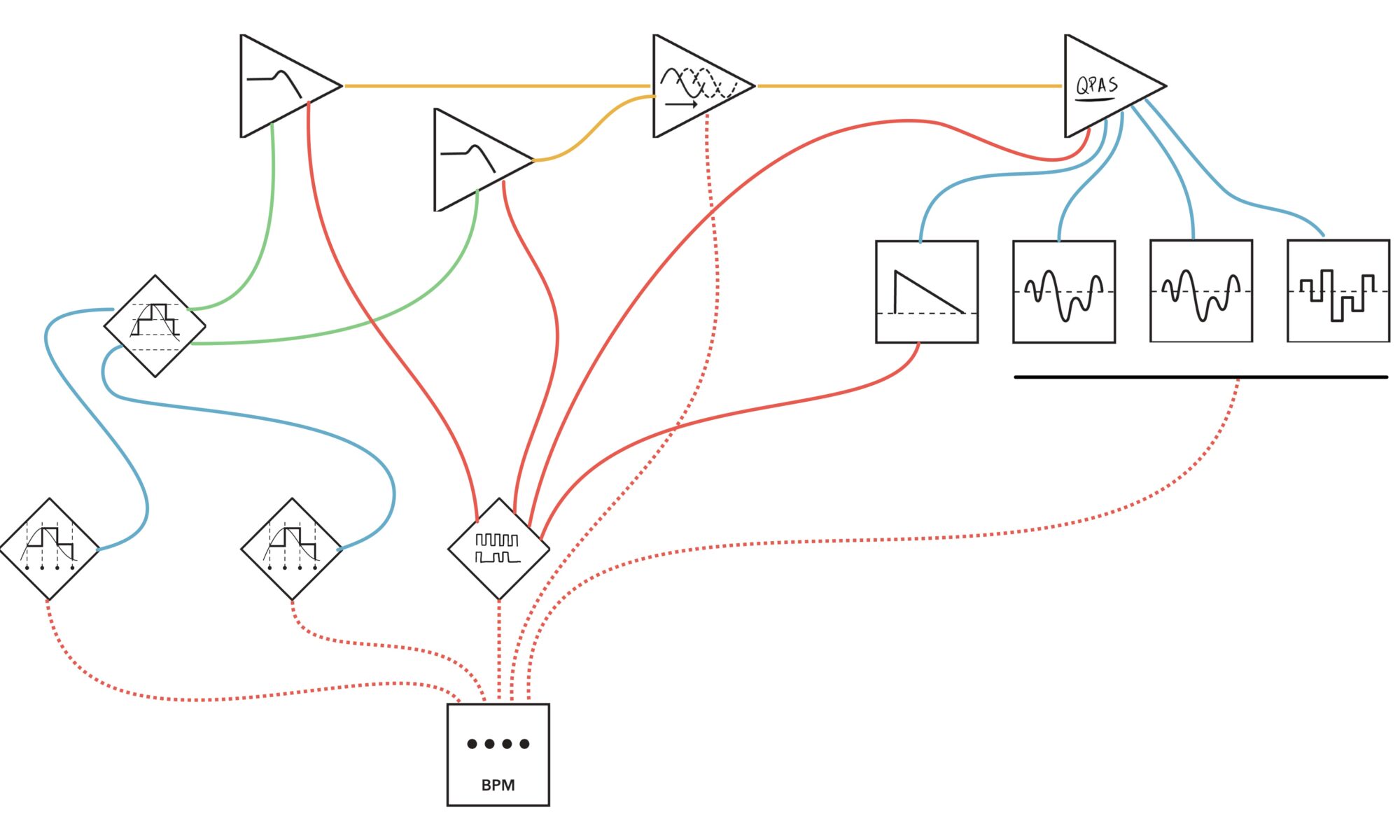

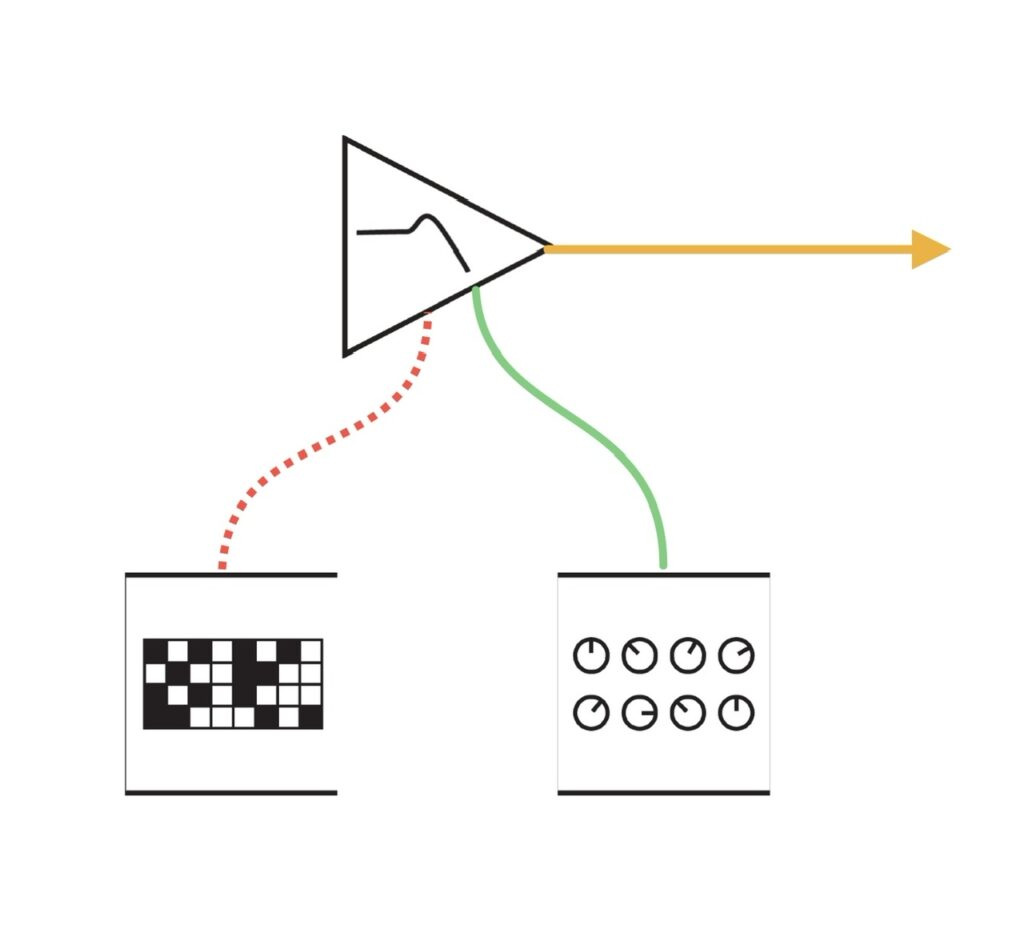

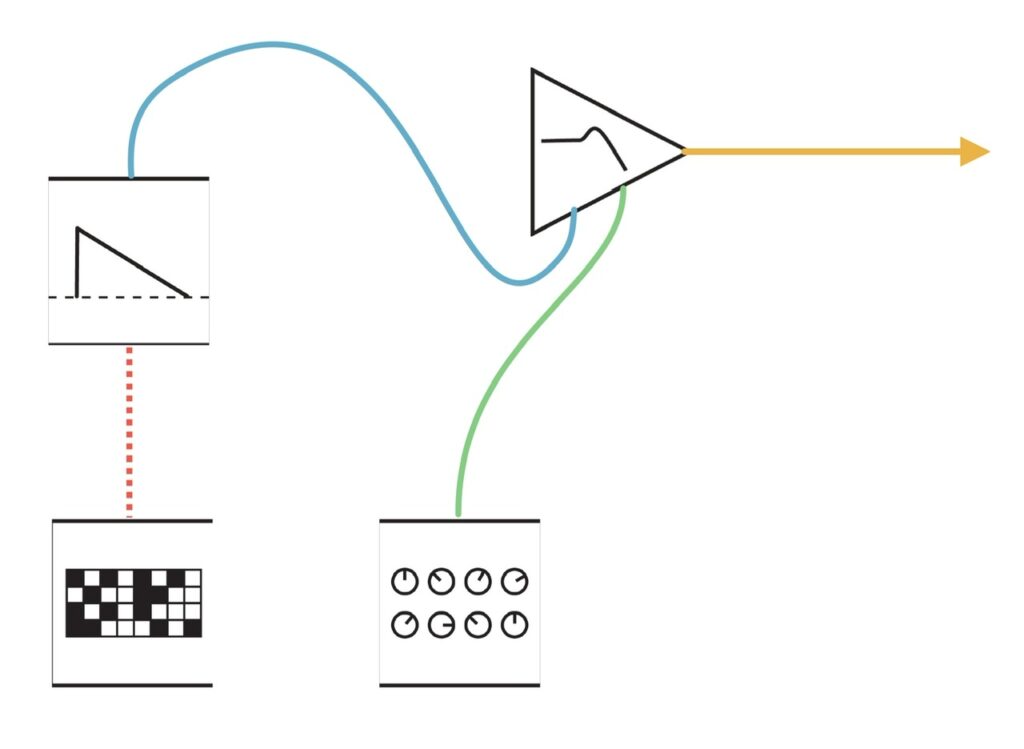

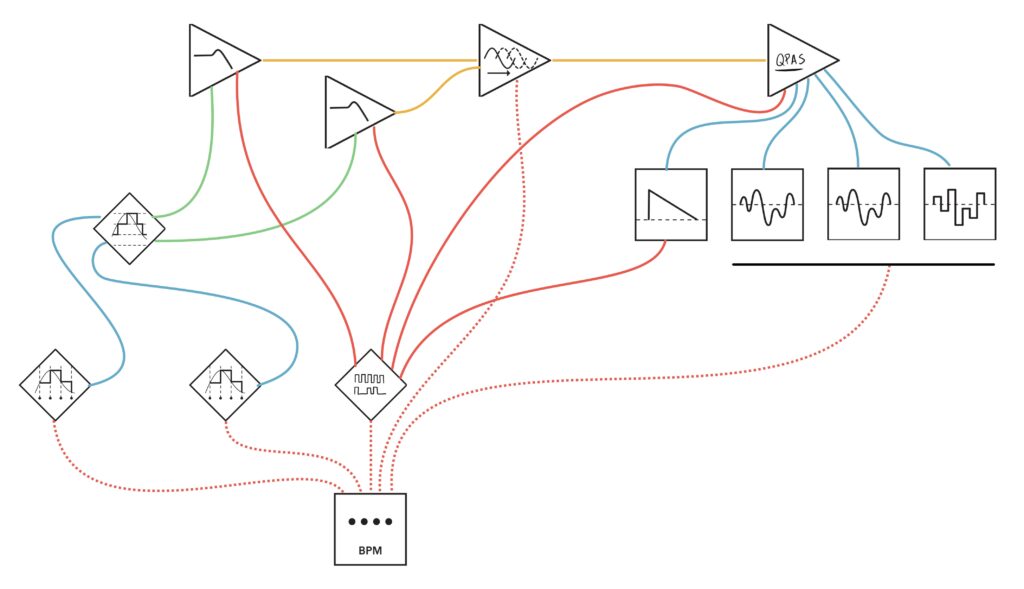

Pianist has its own clock that will change on each beat, along with a clock output to trigger envelopes or some other event as chords change. But it also has a clock input, which will move along the chord sequence with every rising edge like any standard step sequencer. Being that I rarely use a steady clock, I haven’t tried the internal clock, and have instead used clocks created by chaos or some other irregular source. This patch used a fairly complicated sub-patch in order to derive the chord changes. I didn’t want haphazard pitch changes in the midst of notes actively being played, but only when nothing was being heard. Finding an approach for this was time consuming, and although there are probably (certainly?) other methods that would work as well, I settled upon an approach using two comparators, one analog and one digital.

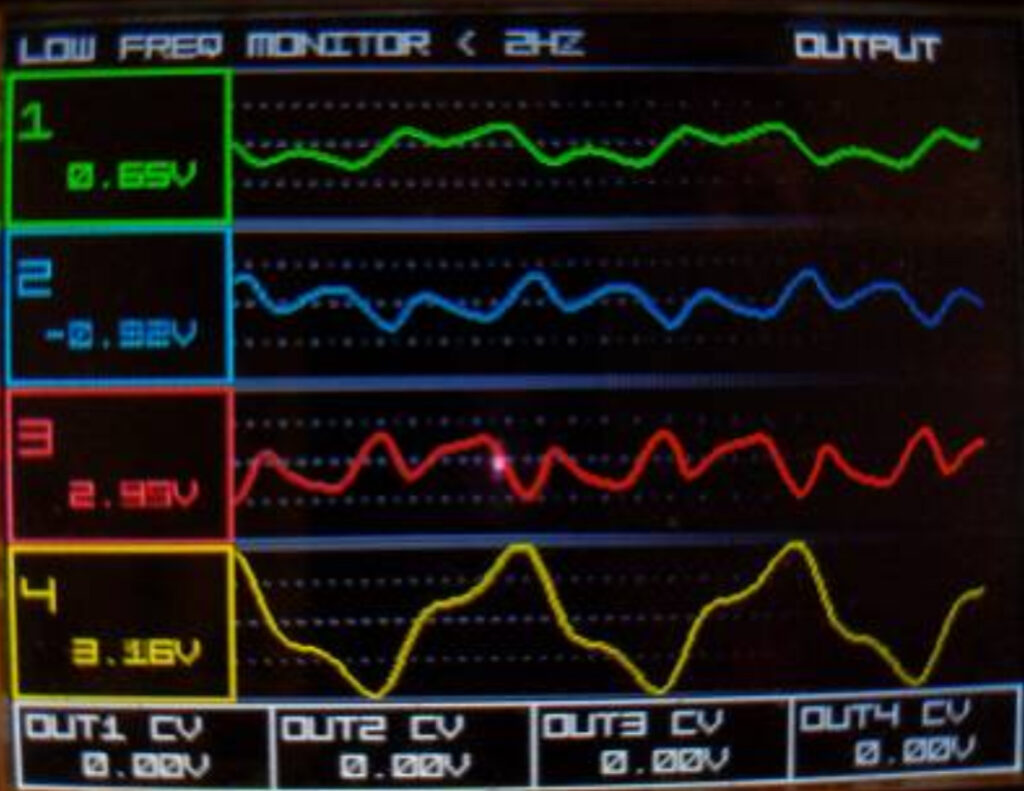

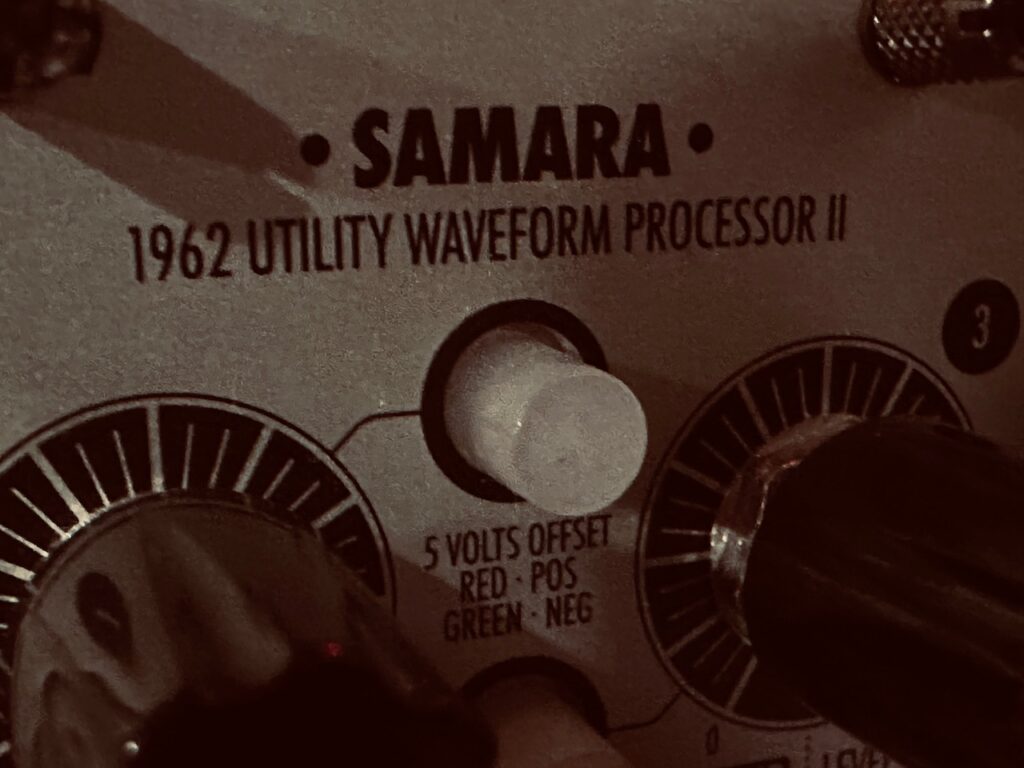

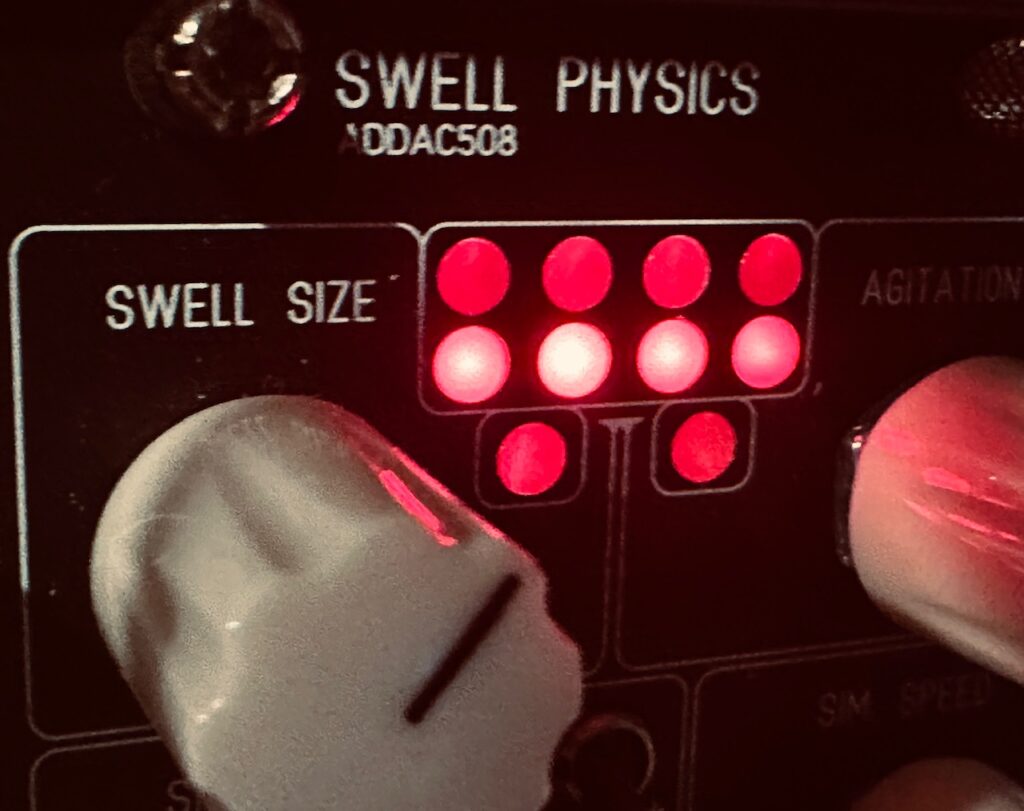

The four waves from Swell Physics first went to the Xaoc Devices Samara II. Samara compares all four inputs, and outputs the Maximum signal (AKA Analog OR). Being that these four waves were controlling the volume of the individual chord tones, it occurred to me that once the Maximum signal went below 0v meant that all four parent signals were below 0v, which meant no volume at all from the chord voice. This is exactly when I want to trigger the next chord in the sequence. I then sent that Maximum signal from Samara II to a digital comparator, the Joranalogue Compare 2, with its compare window set to anything below 0v. So once that Maximum signal went below 0v, it would spit out a gate that would trigger a chord change in Pianist.

The eight chord tones created by the Pianist went to eight different oscillators. The root, third, fifth, and seventh (or fifth if there is no seventh) form the base of the chord and all go to one of the four Flame Instruments 4VOX oscillators, while the color notes and two additional root notes, one that follows chord inversions and one that does not, all go to a self-frequency modulated Frap Tools CUNSA, where each filter is set to self oscillate, and pinged in a Natural Gate.

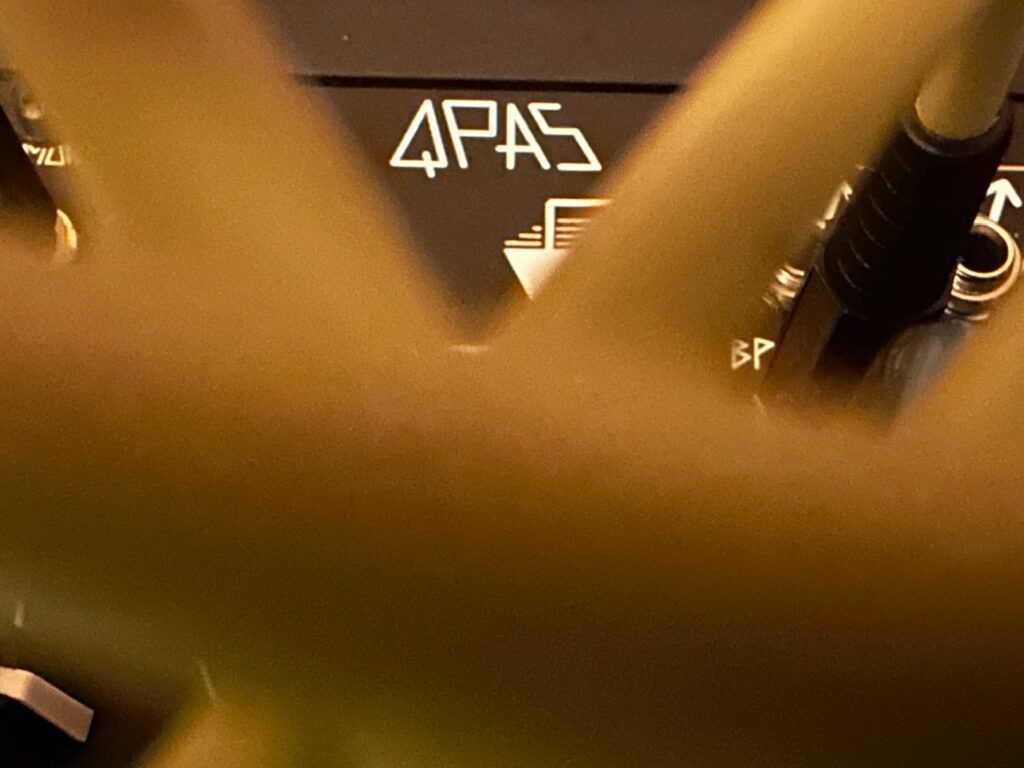

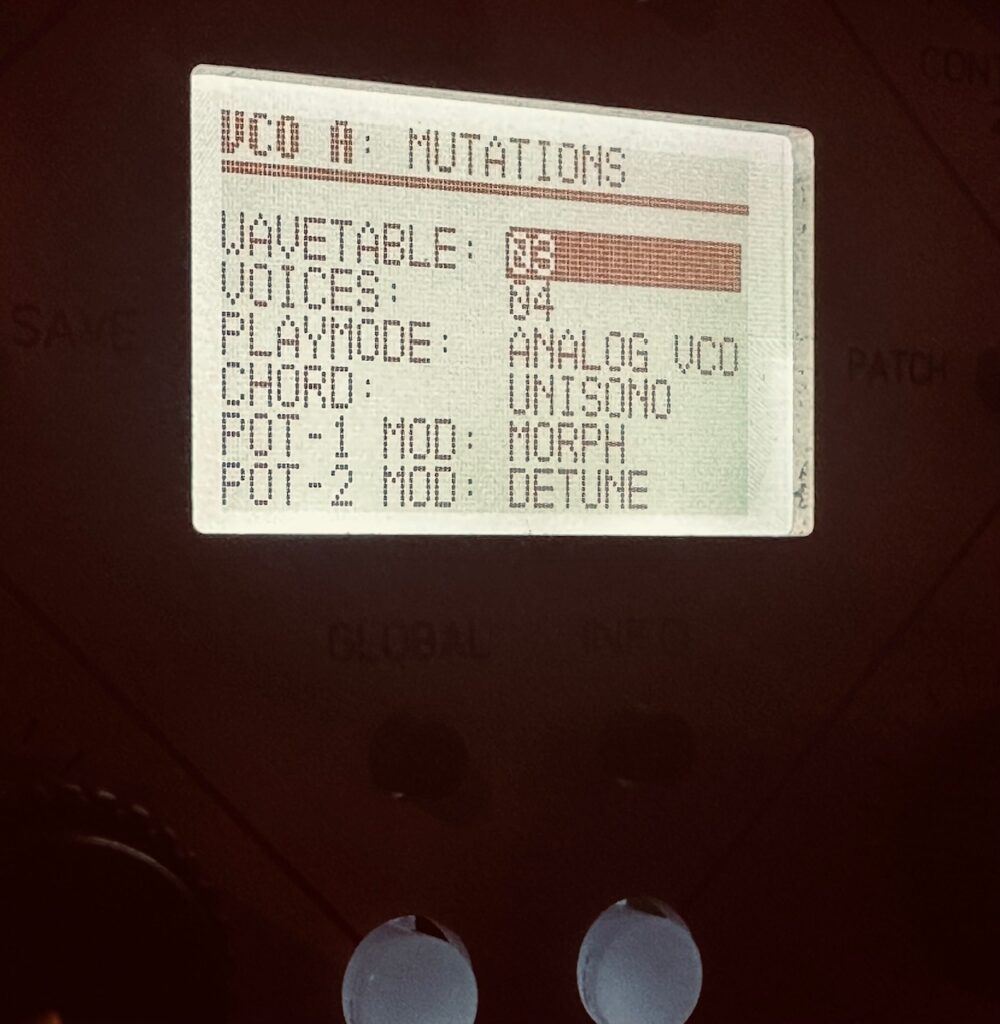

The Flame 4VOX has been around a long time. My brother, a house sound engineer, producer, and DJ who’s been into Eurorack a long time, lusted for one long before I even knew what Eurorack was. It’s a fully polyphonic, wavetable oscillator beast, split into four sections of up to four oscillators each. Each oscillator can create detuned swarms, chords, or be unison. Each oscillator can be controlled by v/oct CV or midi, and is fully polyphonic with its own output. It really was a very advanced piece of gear for its time. It still is, even if it hasn’t been updated in several years and is showing its age. There are two pots and two CV inputs per oscillator that can control several parameters including scanning the wavetable, detuning, amplification, and more. It has internal VCAs to control volume, but I did not like how they functioned at all, and opted to use external VCAs, which worked to my benefit allowing me to modulate two wavetable parameters rather than the volume and only one parameter. There are also separate FM and reset/sync inputs per oscillator, along with its individual output. Even if CV-able options seem to be limited, virtually every facet of the 4VOX can be addressed via midi, although I haven’t used it with midi at all. It’s a very powerful oscillator bank that can cover lots of ground.

Although I wouldn’t say programming the 4VOX is difficult, it’s not as easy as most more modern interfaces. The screen is bare bones with low resolution and a slim viewing radius. The encoder is a little weird. You have to push it down and turn CCW to move downward in menus, while you simply turn it CW to change parameter values inside the menu. As a unit, it’s impressive. There are lots of options, plenty of stock wavetables to choose from, and it sounds good, but it shows its age. Upgrading firmware is a laborious process with modern computers. Although you can install your own wavetables, the processes to convert them to the right format and get them loaded can be a nightmare, particularly if you’re a Mac user. All of the computer-side software is a decade or more old, and workarounds are sometimes needed. I’m not a “I need to load my own wavetables” kind of guy, and my unit came to me with the latest update, but if I were that guy or my unit hadn’t already had the latest firmware, it would not be an easy task. I’ve had similar problems with older gear before3, and they’re no fun.

The 4VOX forms the base of the chords, brought in and out by the four waves from the Addac508 Swell Physics. The sound is both powerful and delicate, with each quadrant set to four slightly detuned, unison oscillators, each one being slightly modulated by the Nonlinearcircuits Frisson. Although I was pleased with the 4VOX’s performance, the Synthesis Technology E370 is a better overall option. Although the E370 is also based on nearly decade-old technology, it’s still a better user experience. The screen is in color, fully customizable, bigger, and gives more information. The stock wavetables are a gold standard. The software UI is easier to navigate using a more standard encoder. The physical UI is also far better arranged. With the 4VOX, the screen is in the middle of the module, knob locations are not symmetrical, and are more difficult to wiggle once everything is patched up. The E370 has everything laid out very neatly. The screen is on the far left, I/O on the far right, with knobs in the middle, leaving more than enough room to wiggle. It’s really a premium user experience. The only advantages the 4VOX has are its price, size, and complete polyphonic midi capabilities. The 4VOX has always been less expensive than the E370, and that remains true on the secondary market. However, the price differential on the used market is much closer than their respective MSRPs, as the E370 can be purchased for well under 50% of the original retail cost. The price difference on my units, both purchased used within a week of one another, was $100. The size, however, cannot change, and in that regard the 4VOX has the E370 soundly beat. At 29hp the 4VOX is still large (and odd hp 😕), but it’s dwarfed by the massive 54hp E370. It’s the massive size, however, that makes the E370 such a pleasure to wiggle.

Once mixed to mono in the Atomosynth Transmon, the 4VOX chords went through the venerable Industrial Music Electronics Malgorithm MkII, a powerhouse FSU-type module with bit crushing, sample reduction, and various types of waveshaping available to have anything from subtly crunchy through completely mangled audio at the output. Using Malgorithm was an absolute treat. Most of the lo-fi effects I tend towards are of the vintage variety, tape sounds, record pops, etc, vs just slightly old sounding digital artifacting, so it was a different sort of experience. On any other day I likely would have chosen distortion in this role, but the day I started this patch I precipitously chose to go with a different kind of dirt. And it was perfect. I was still able to get some nasty distortion via the “Axis” waveshaper (whatever that does), with the bit crushing and sample reduction playing a slowly increasing role. It’s starts clean, then moves to understated digital artifacting, and finally waves of full blown destruction, ending clean once again. One aspect of Malgorithm I enjoyed was the interaction between input level and the waveshaping. It responds similarly to tube distortion circuits, where the harder you drive the input, the more distortion there will be ranging from just barely there to outright obliteration. Each of these waveshaping circuits has three different levels, red, orange, and green, and all of them have their own character. These waveshapers can even interact with each other for nuking your audio from orbit if that’s what you want. I rode faders on the very awesome Michigan Synth Works XVI to control both the input level as well as the wet/dry mix in order to provide a performative aspect to this patch. Both the bit crushing and Nyquist parameters were modulated by the Addac506 Stochastic Function Generator, with a fairly wide range of both rise and fall times between medium and long. Each of the parameters were set to moderate crunchiness with the knobs, with their modulation moving towards a full-resolution signal. This created an absolutely amazing effect from the sound of dying batteries to the fabric of the universe being unzipped and sewn back together. I would highly recommend Malgorithm to anyone, but you’d have to find one first.

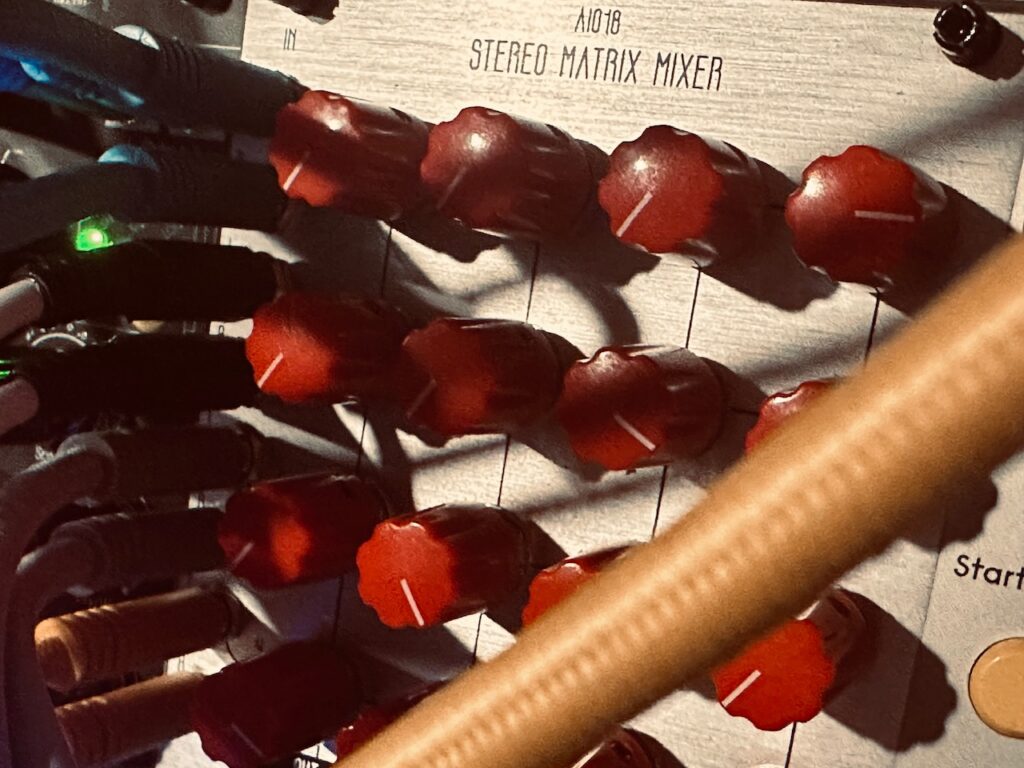

Once through Malgorithm and into the stereo matrix mixer, these now buzzy chords went to the Holocene Electronics Non-Linear Memory Machine, with a very light perfect fifth shimmer in the feedback loop. I initially went with a full octave shimmer, but decided against it as it was too prominent and spiraled too far out of control too quickly. This created a very subtle sheen on the chords that isn’t noticeable much of the time, but is a nice effect nonetheless. Feedback and Spread were both modulated by attenuated versions of the Average output from Swell Physics.4

The color tones of each chord were all sent to the mighty Frap Tools CUNSA, a quad filter extraordinaire, and pinged in a pair of Rabid Elephant Natural Gates. Though I was tempted to use the simple sine waves from each LPF output, I later decided to use the HPF output as a means of each oscillator frequency modulating itself in order to add some harmonics, which worked a treat. In retrospect, I could have simplified the patch significantly had I pinged CUNSA itself instead of running the output to Natural Gate, but I chose the Natural Gate route because Natural Gate.

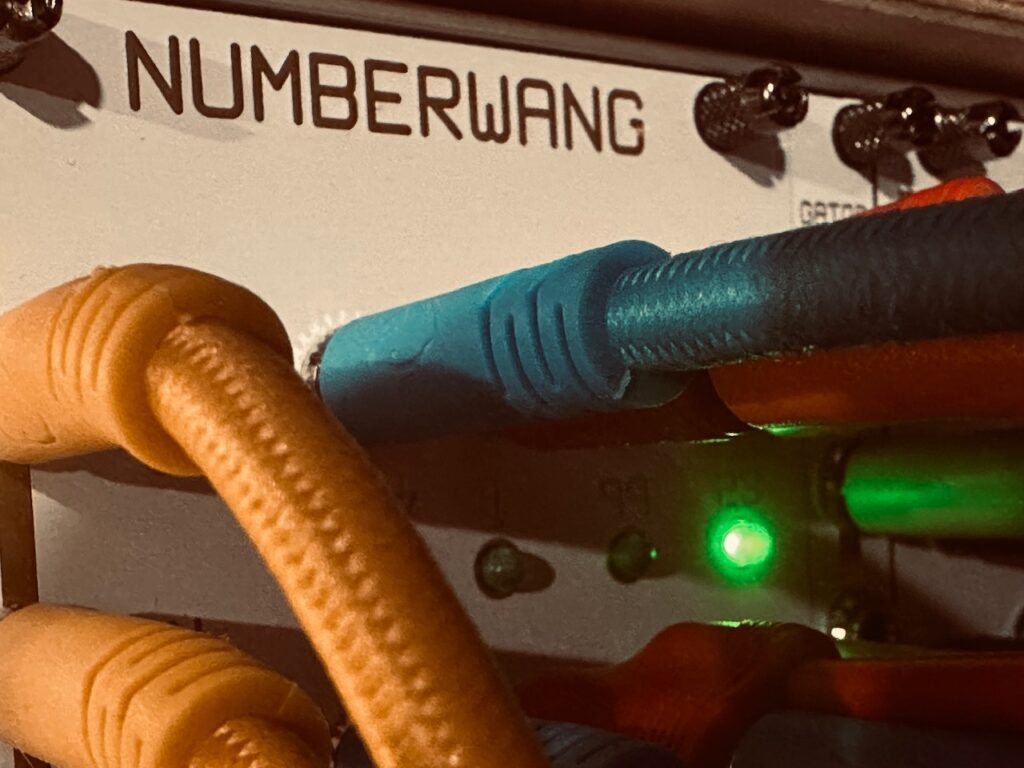

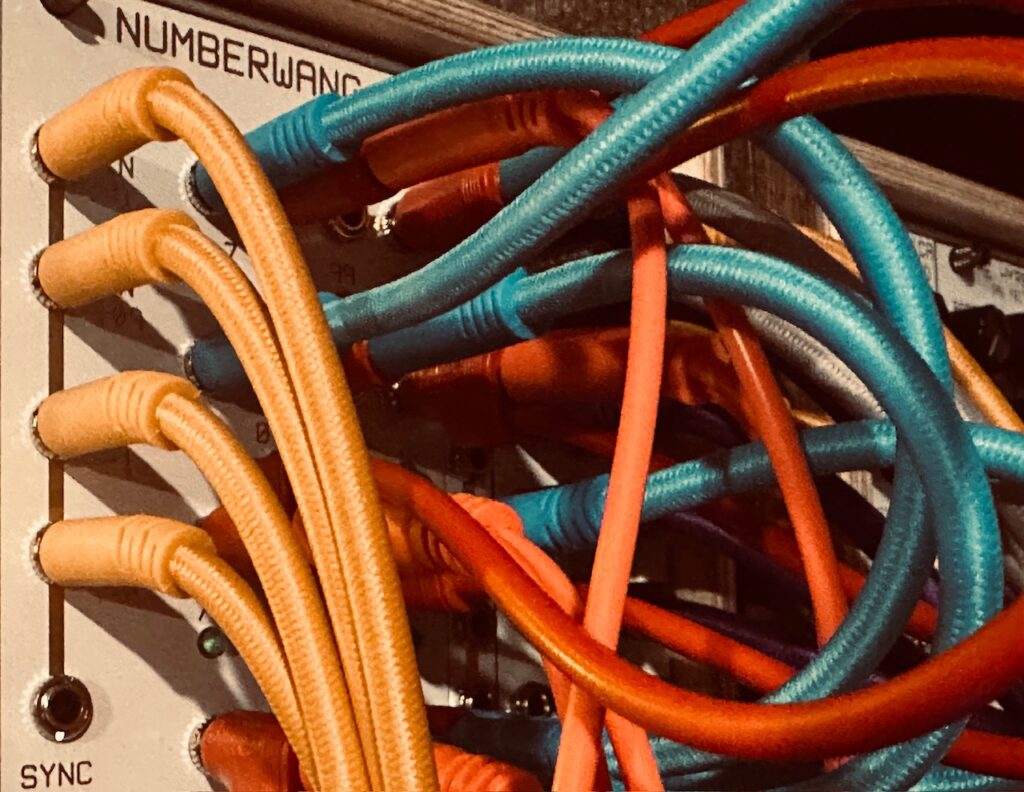

Using a patch technique I’ve used often, the gates that pinged the Natural Gates were created by running the four waves from Swell Physics into the Nonlinearcircuits Numberwang. But rather than simply choosing four gate outputs, I ran several Stackcables so that each strike input on the Natural Gates were each derived from three Numberwang outputs. This filled in space much better. The notes are still sparse, but they’re triggered at a much better pace using three gates each rather than just one. These notes fill out chords in interesting ways. They’re very short, but combined with delay and reverb, those colors hang around long enough to create intrigue in the overall sound without being intrusive.

These notes were sent to what is becoming one of my favorite delays, the Chase Bliss Audio Reverse Mode C, a re-imagining of one of the modes on the legendary Empress Effects Superdelay. Although it certainly does standard stereo delay stuff, it excels at being a quirky sort of delay, able to output normal delays, reverse delays, and octave up reverse delays, by themselves, or in a mix. Mixing delays creates a beautiful sound space of echoes bouncing all around the stereo field, at different speeds and octaves, which is an incredible aural treat. I haven’t yet learned to properly modulate the Reverse Mode C, but that’s a function of not having a firm grasp on midi. As I figure that out, things ought to get very interesting, with different sorts of delays fading in and out in very creative ways.

The last synthesized voice in this patch is the Good and Evil Dradds as an effects send, sending both the chords and ornamental color notes for some granular action. The Dradd(s) outputs went to separate EF-X2 tape echoes with different settings. Ever since getting a second Dradd, I’ve been infatuated by what I can do with them, and this patch may be the best result yet. Both were set to Tape mode with similar P2, but different P1 knob positions, with the P1 parameter on both being modulated by an attenuated version of the Average output on Swell Physics. The Dradds, in some ways, steal the show. They create all sorts of movement in the stereo field and fill the space between chords and color notes in ways that keep the piece from becoming still. They’re the wake left after a large swell passes by. The bio-luminescence after a crashing wave.

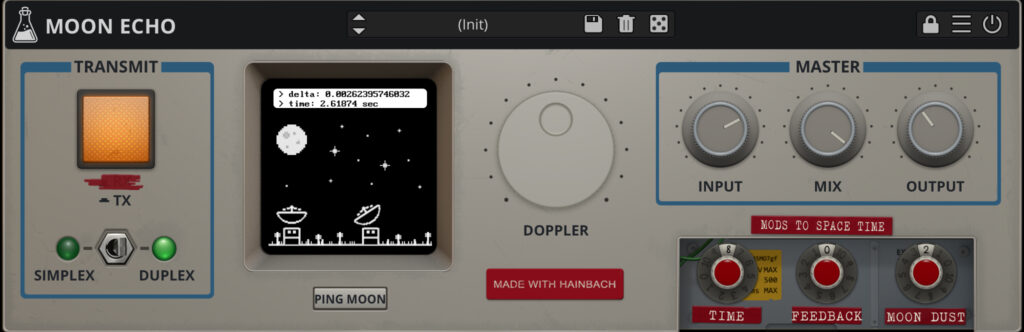

The spoken voice is a set of three samples that were triggered in Koala on the iPad. Triggers emanated from the gate outputs on Swell Physics combined in the new Nonlinearcircuits Gator, sent to the Joranalogue Step 8 and then the Befaco CV Thing and converted to midi notes that were sent to trigger Koala samples on the iPad. It took me a while to figure this one out, though it worked exactly how I envisioned. Gates from Swell Physics were combined in Gator, which triggered Step 8. Each of the first three steps sent its individual gate output to a different CV Thing input. This ensured that the three samples were always triggered in the correct order. The samples themselves were then sent to a new collaborative delay plugin, Moon Echo, by AudioThing and Hainbach.. Moon Echo is a modeled simulation of bouncing sound off the moon, and has a very distinct character. The delay was set to fully wet, and has a delay of about 2.5sec, though that changes depending on the day. The moon is not at a fixed distance from the earth, and the plugin reflects that. By “pinging” the moon upon startup, you will get the current distance to the moon, and a new delay time down to five decimal points (1/100,000 of a second). Fucking cool.

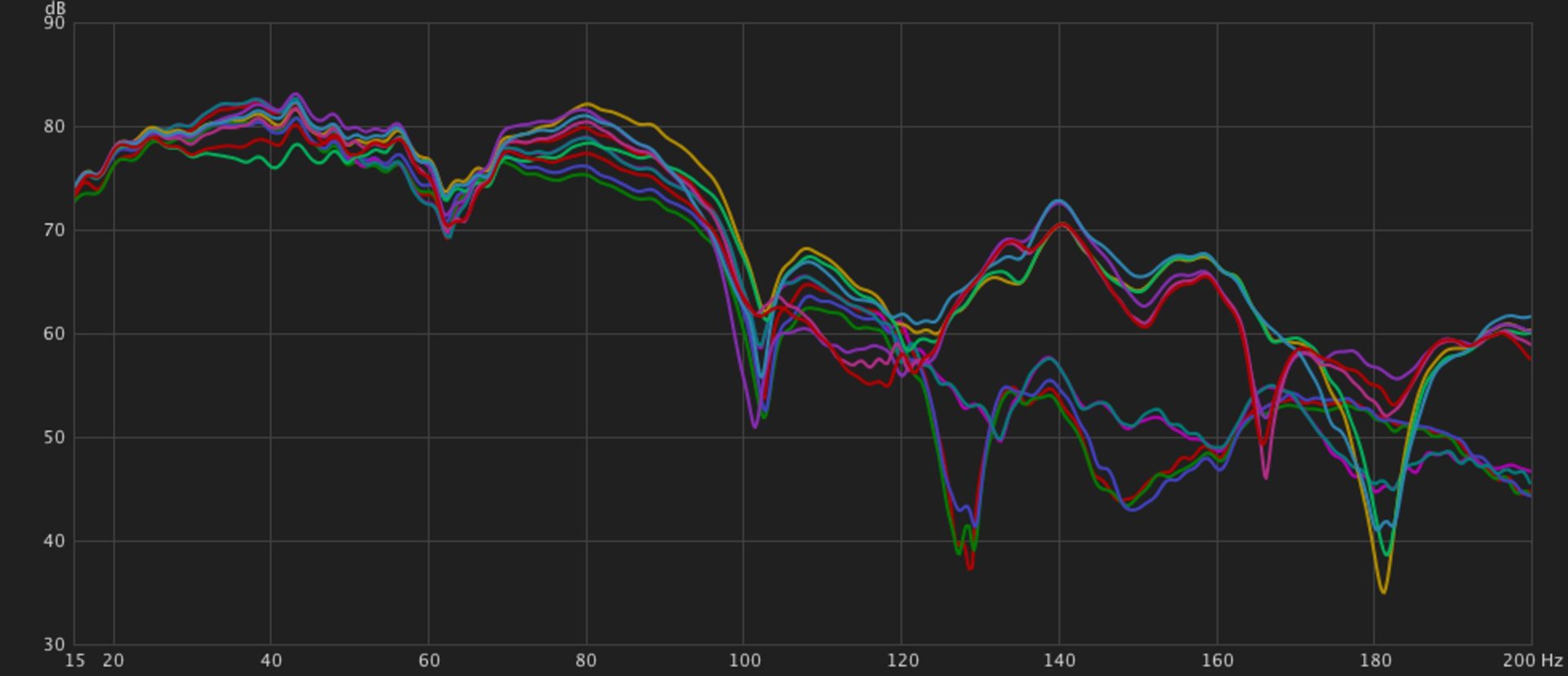

One thing I did differently with this patch paid off high dividends, and will absolutely become a staple in my recordings. I’ve been patching for a few years, but am still an absolute novice at standard studio stuff. Mixing, EQ, compression, and everything else in that sphere evades me. I’ve used some very basic EQ in the past, but really only on the final output, which, as I’ve discovered has several drawbacks. This patch was the first I’ve ever recorded using EQ, the highly regarded Toneboosters TB Equalizer 4, on individual channels as they were being recorded. The chords, ornamentals, and reverb send received EQ that greatly improved the sound quality, even if it could still be better. I did, however, neglect to put EQ on the Dradds, which proved to be a mistake, as there is a very occasional pitch that pierces through in what can’t be far from dog whistle frequencies. It’s not eardrum busting, but I can hear it, and it annoys me. I didn’t catch that behavior when recording, and never EQ’d it out. That said, it was also the first time I’ve recorded a modular patch in separate multi-tracks, including the chords, ornamentals, Dradds, spoken voice, reverb return, and the mixed stereo signal (presented here). I can go back and make changes or additions should that be something I want to do, or send the parts to someone else for mixing and mastering should I ever choose to release it.

Overall I’m very pleased with this patch. It was originally composed in a different key and completely different chord progression, and for a special group of online friends. The chord progression I used in this recording wasn’t composed, as such. At least not by me. I asked ChatGPT for a “sad progression, yet with a sense of hope.”5 I asked for it to be more sad, and it changed key from Amin to Dmin, and ended in a non-diatonic chord (DMaj), which I found a wonderful “choice.” Then, as a means to test the Pianist, I asked for several chord extensions and inversions, and ChatGPT complied, giving us what we have in the recording.

Modules Used:

Addac Systems Addac508 Swell Physics

Addac Systems Addac506 Stochastic Function Generator

Flame Instruments 4VOX

Frap Tools CUNSA

Frap Tools Falistri

AI Synthesis 018 Stereo Matrix Mixer

Atomosynth Transmon

Industrial Music Electronics Malgorithm Mk2

Holocene Electronics Non-Linear Memory Machine

Pladask Elektrisk Dradd(s)

Nonlinearcircuits Numberwang

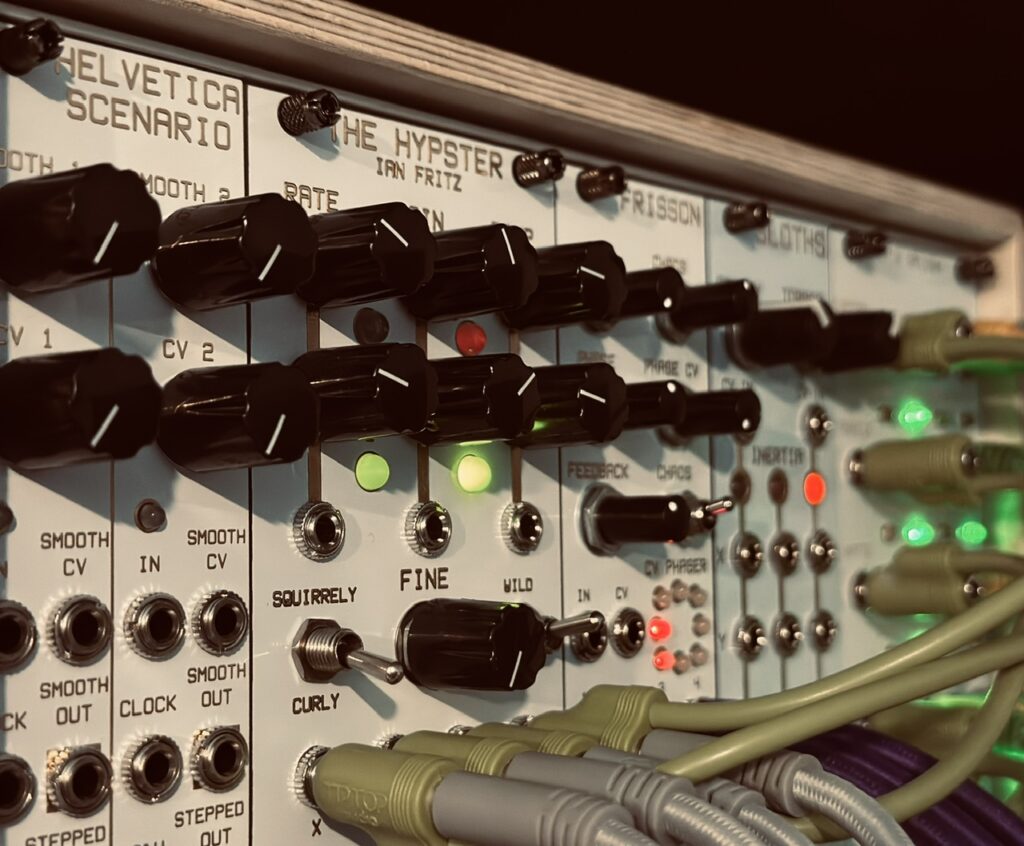

Nonlinearcircuits Frisson

Nonlinearcircuits De-Escalate

Nonlinearcircuits Gator

CuteLab Missed Opportunities

Rabid Elephant Natural Gate

Joranalogue Compare 2

Joranalogue Step 8

NOH-Modular Pianist

Befaco CV Thing

Intellijel Amps

Xaoc Devices Samara II

ST Modular Sum Mix & Pan

Outboard Gear Used:

Echofix EF-X2

Chase Bliss Audio Reverse Mode C

Walrus Audio Slöer

Michigan Synth Works XVI

Plugins Used:

AudioThing x Hainbach Moon Echo

elf audio Koala Sampler

Toneboosters TB Equalizer

Improvised and recorded in 1 take on iPad in AUM via the Expert Sleepers ES-9.

- I studied music performance in college, and have a decent grasp on music theory. The last 30 years, however, have pared that knowledge down to basics. I’m certainly no expert, but I can read chord charts and identify chord notes, even if I have to think for a second. ↩︎

- Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, etc ↩︎

- The Humble Audio Quad Operator I purchased did not have the latest firmware update, and the internal VCAs all bled badly. I was unable to install the latest firmware with a modern Mac. I was fortunate to have an older one available to me that I was able to use. ↩︎

- There are no fewer than seven modulation points in the patch that are all modulated by an attenuated version of the Average output from Swell Physics. ↩︎

- This was literally the first time I’ve ever considered purposefully using AI for anything. ↩︎