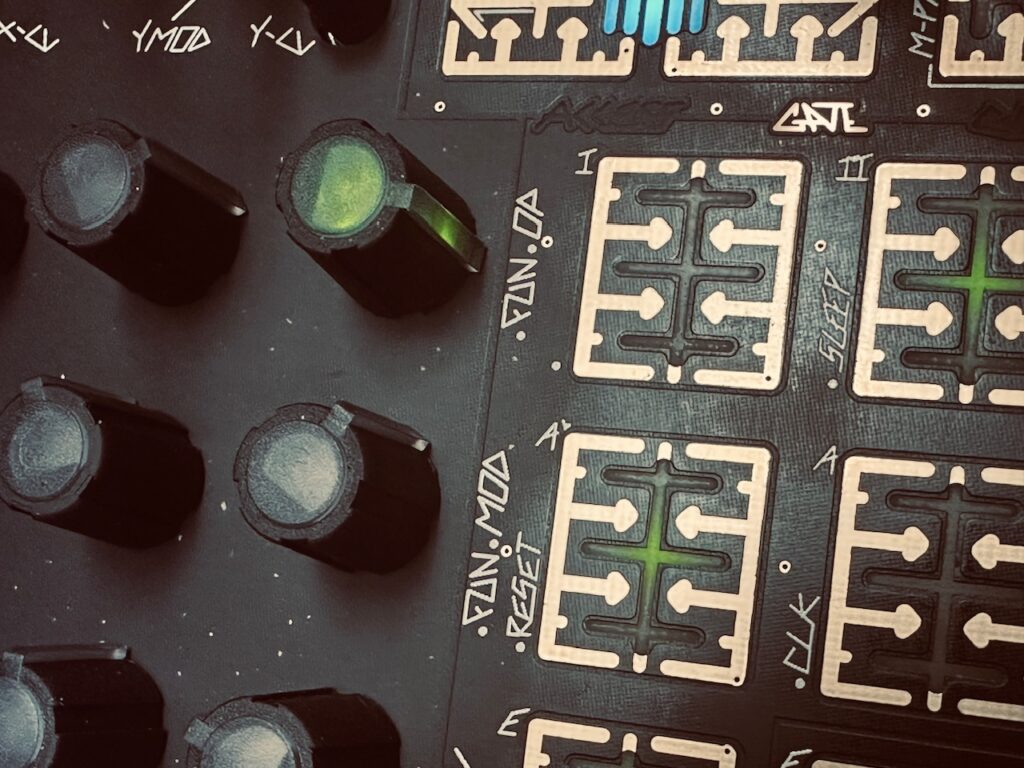

I’ve had a full Make Noise synth for a while. In fact, I had far more Make Noise modules than I had space for, and with the recent release of Multimod, their new modulation tool, I decided to spring for a second 4-Zone CV Bus Case to avoid having to constantly rearrange the case from patch to patch. Multimod is an interesting tool. Billed as an eight output buffered multiple with several tricks up its sleeve, it presents a new method of spreading modulation signals around a case. It uses phasing, time, and speed manipulation in order to conjure this newfound magic. Fugue-like sequences can be created, as can wild modulation schemes, and many other things besides, all created from a single input signal. Being a Make Noise fan, I ordered one knowing only that it was a modulation source. If Make Noise has a gap in their lineup, it’s modulation sources. Once I saw the initial demo videos by Sarah Belle Reid and Red Means Recording, I ordered a second.

Although upon receiving them I used the new Multimods briefly to get an idea of how they worked, I hadn’t yet delved into what they can really do. I roughly recreated a couple of patches found in the videos, such as sending a sequence to several oscillators, and even trying it as a multitap, pitch shifting delay, but these were surface level primers, not any sort of real exploration. Being that Multimod presents a very new way of sending modulation around a synth, I was unsure how I might want to use them. My initial thought in ordering two was to use one for CV manipulation, and the second as an audio processor. I’ll certainly do more of that in the future, but I wanted to see if I couldn’t tackle an issue I noticed right away.

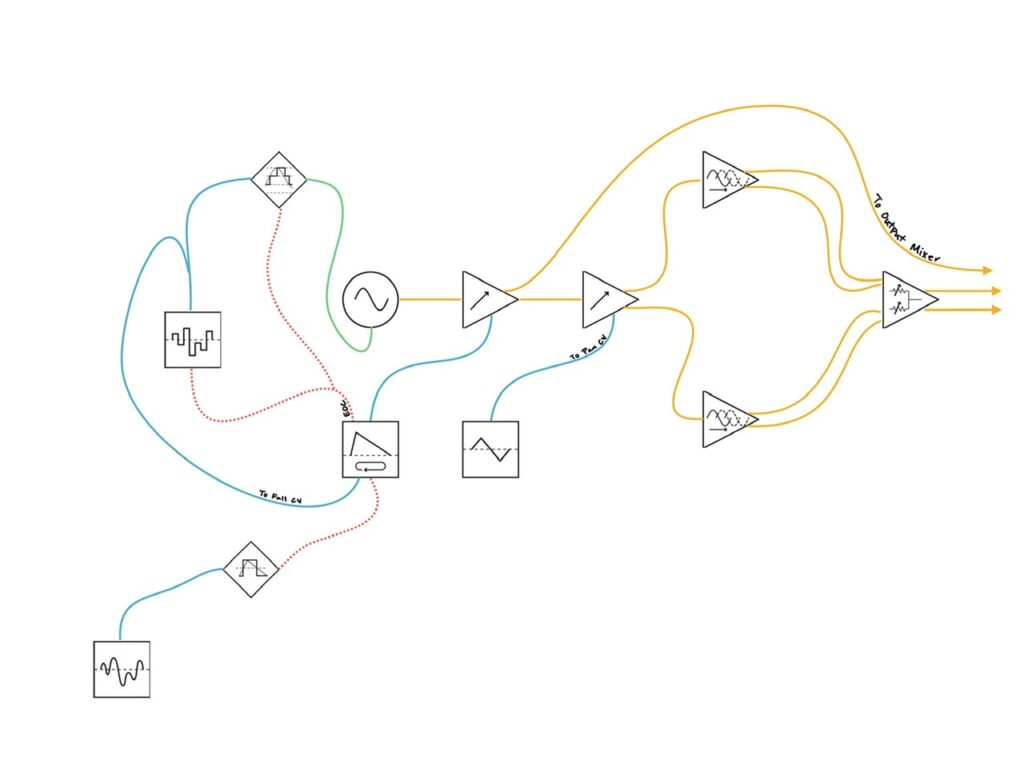

One of the highlights of the video demonstrations were the creation of fugue-like sequences, where many oscillators would receive the same sequence, but at different speeds or phased in time in interesting ways. But I also noticed immediately that although the sequence pitch data was spread around, there wasn’t a good way of spreading around an accompanying gate sequence for articulation. Some attempts at remedying this conundrum that I’ve seen involve using a separate gate sequencer, or even just a clock. And while deriving pitch and gate sequences independently is a particular strength of eurorack, that method seemed haphazard and insufficient for this application. I wanted more. I wanted the entire sequence at all of the outputs regardless of the speed or phase. So I thought about it, and suddenly a potential answer came to mind. Use one Multimod for processing the pitch sequence, and the other for processing the gate sequence. But there was still the problem of movement. I needed to move the knobs the exact same amount at the exact same time in order for the outputs on both modules to follow. How would I modulate them so that they were always doing the same thing at the same time and the gate sequences were following their pitch CV counterparts?

The CV Bus.

Although a Maths channel two or three could be used as an offset in the same way, I decided to use the CV outputs of the Noisy Fruits Lab Lemon, a very excellent standalone CV/MIDI controller, to manually control Multimod’s Time and Spread controls. My goals here were simple: to use two Multimod’s to control a single René CV and gate sequence, with the outputs on both being in sync with one another. If Multimod were an all analog module, I think this experiment would likely be dead in the water. I’m not convinced that parts and control tolerances would be close enough such that they would remain identical through modulation. But since Multimod is all digital, I surmised that so long as all of the Init settings were the same on both, they should (very theoretically) react the same to identical control voltage received at the same time.

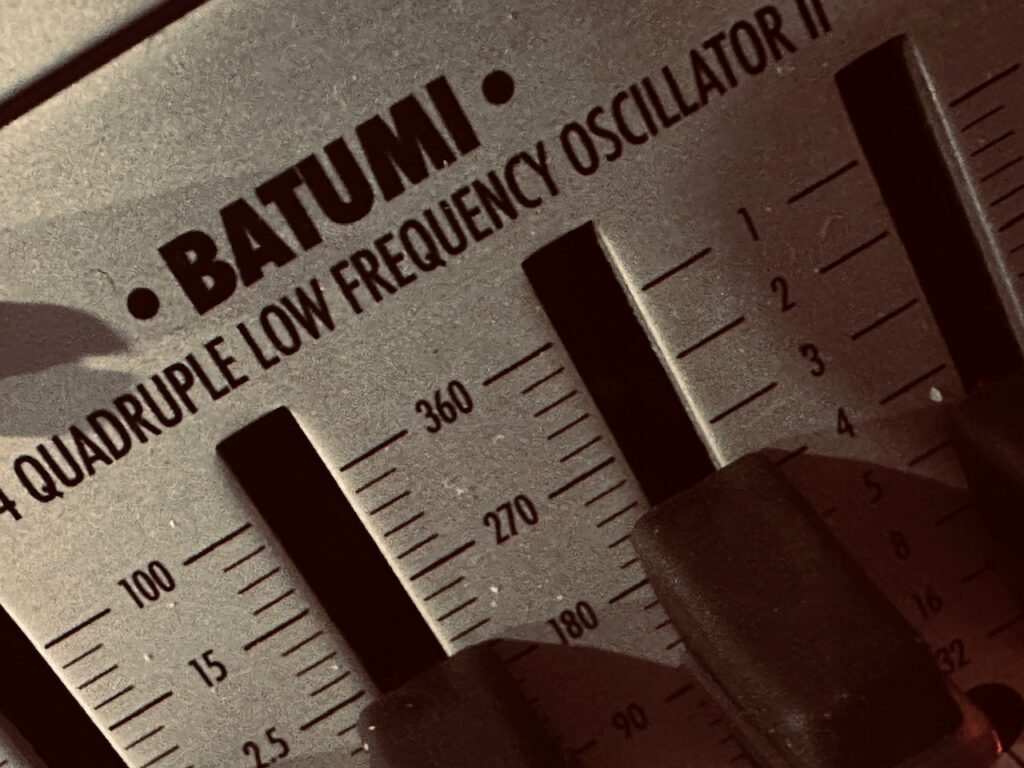

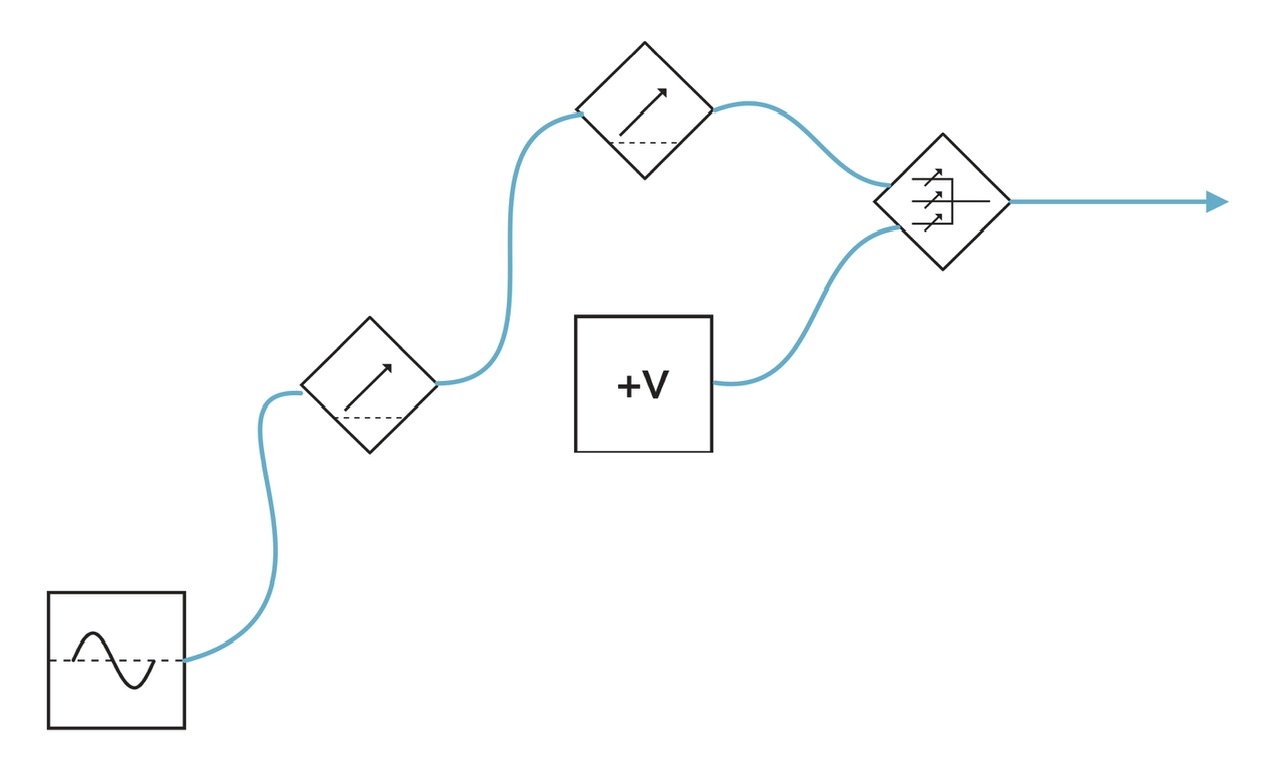

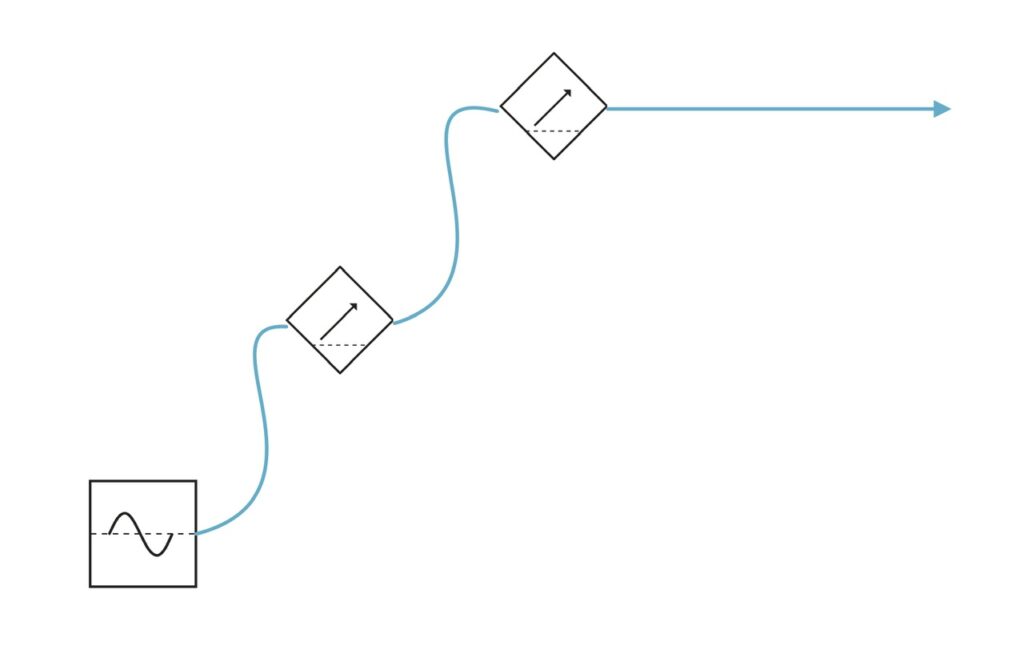

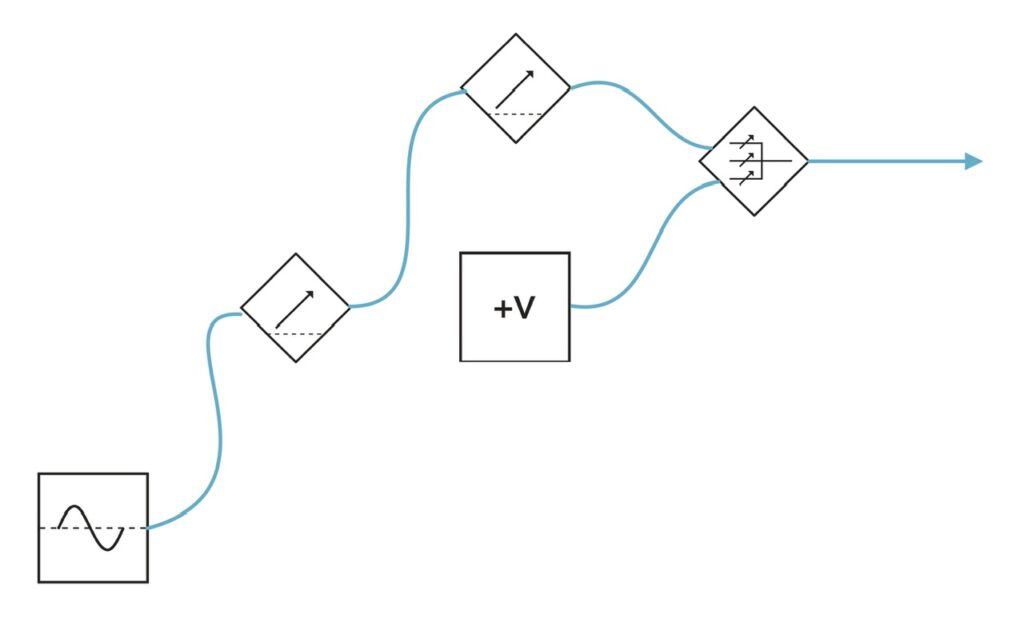

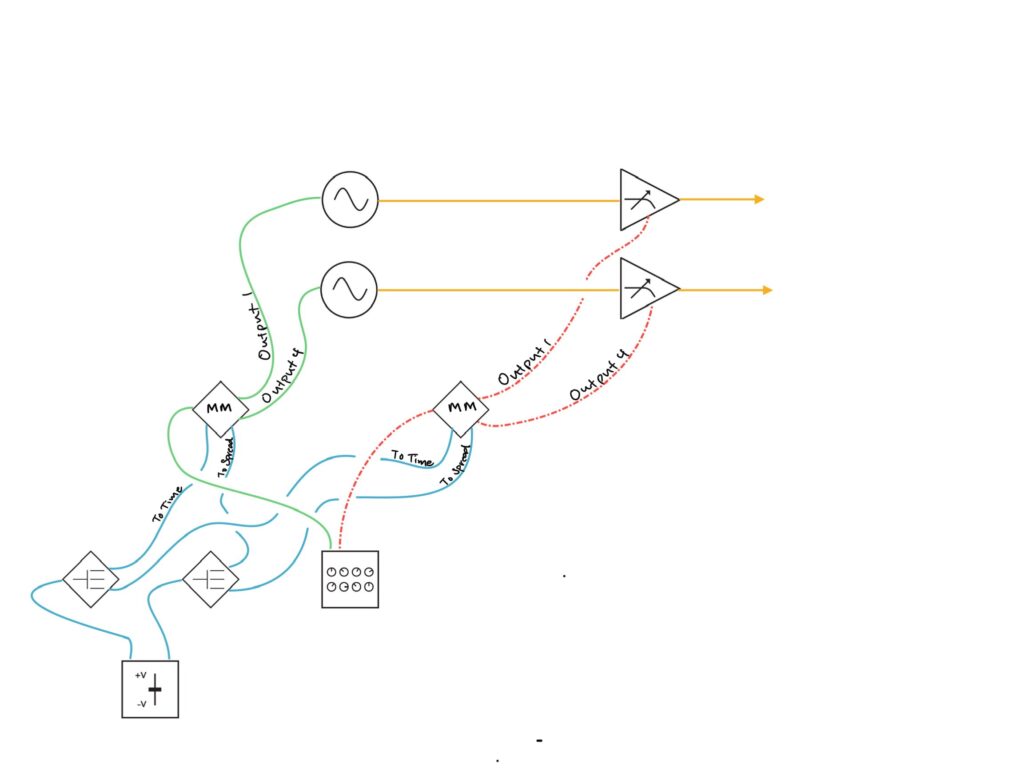

To start, I copied a x2 clock from Tempi to both Multimod Tempo inputs, with a second /16 clock to both Reset inputs. This ensured that the clocks of both units would always be in sync. I then patched René’s X CV channel to the first Multimod input, and the X Gate output to the second Multimod input. The Init setting on both Multimods were simple: Phase at full CCW, Spread at Noon, with the Spread CV attenuverter at full CW, and Time at full CCW. With these settings, things worked just as they should: a single CV and gate sequence from all eight outputs happening at precisely the same time. So far, so good. I then patched the Lemon fader CV outputs to the CV Bus, and then to both the Time and Spread CV inputs on both Multimods.1 A single CV source should (again, theoretically) modulate both units identically such that as the CV sequence speeds up (or slows down), the gate sequence simultaneously does the same, and corresponding outputs on each Multimod should remain in sync.

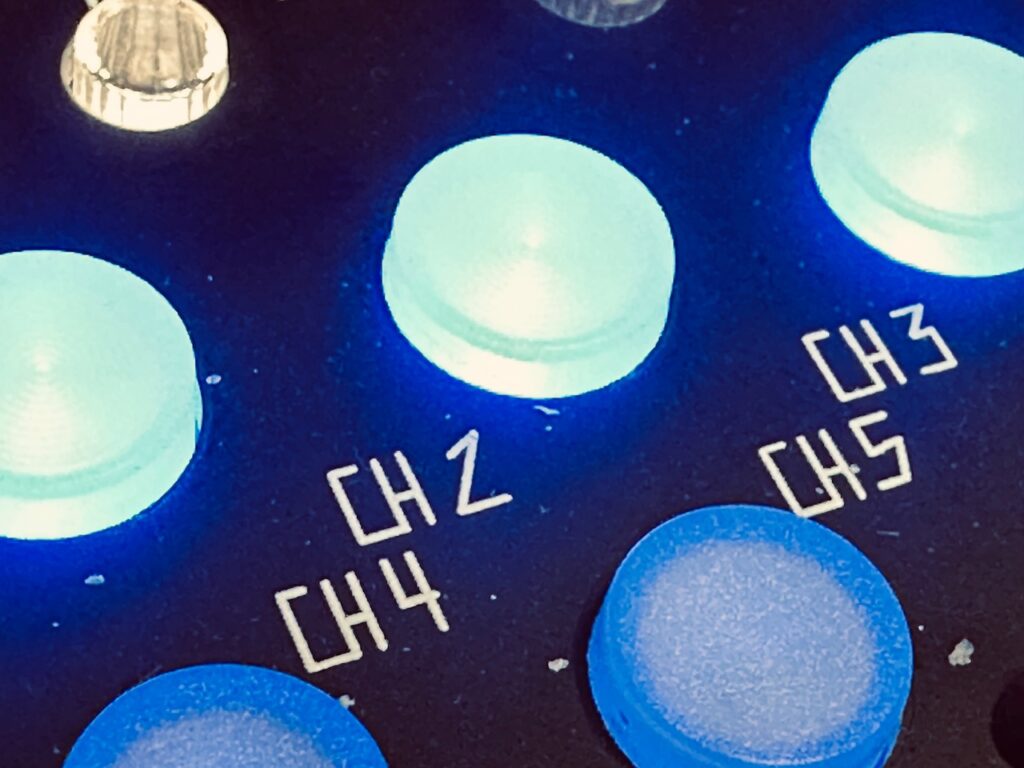

For the oscillators I chose the Spectraphon.2 The first Multimod output one was patched to Oscillator A, with Output four patched to Oscillator B. The mixed outputs of each side of Spectraphon were then patched to QMMG inputs one and two. Outputs one and four of the second Multimod were patched to QMMG’s CV inputs, with both QMMG channels in LPG mode (though it sounded cool in LPF mode too). With identical modulation going to both the Time and Spread CV inputs of both Multimods at the same time, the CV and Gate sequence outputs should (theoretically) also be in sync with changes. The CV sequence from output one on the first Multimod should match the gate sequence from output one on the second Multimod. Ditto with the other outputs.

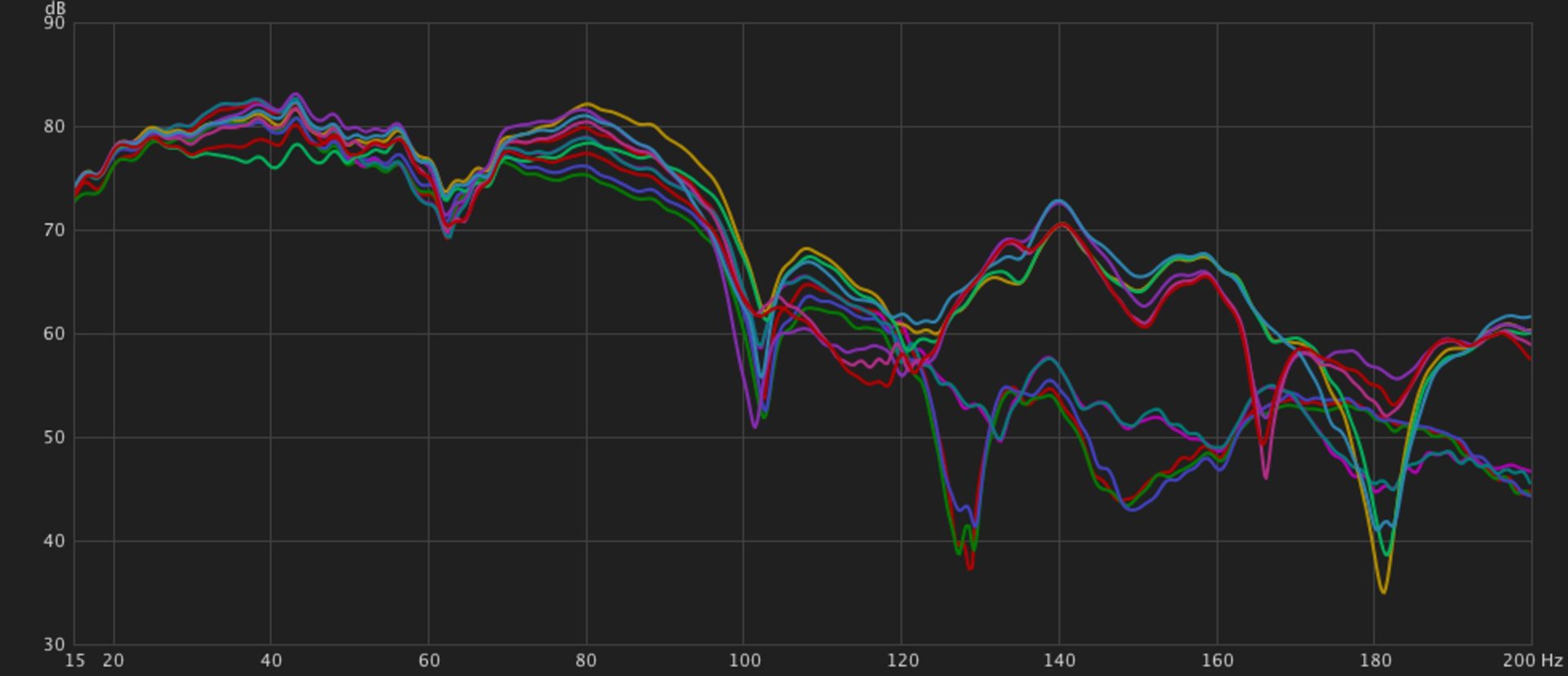

To be honest, I’m not sure if the patch worked like it should have in theory. What I mean to say is that the result is ultra-cool whether theory was borne out in practice or not. Things sound correct with the resulting sequence from Multimods output four, the output that is affected least by changes to Time and Spread. But I can’t really tell if the pitch and gate sequences from Multimods output one, the output affected most by changes to Time and Spread, is synced in the same way. The sequence is moving pretty fast. Hearing individual triggers can be tough at super high speeds, especially when slamming triggers into vactrols, like those in QMMG. Not only is there inherent bleed, but the fall response is such that you can’t always hear individually triggered notes if they’re in quick succession. DXG would likely have been a better candidate for testing the precision of the altered sequence because each trigger is annunciated clearly in a way that isn’t possible with vactrols. That said, I’m a huge fan of vactrol bleed. It can be a beautiful effect when used with intention, and although I wasn’t looking for any particular sound with this patch, vactrol bleed certainly showed off its character in this test recording.

The QMMG outputs were sent to X-Pan, with the Channel four sequence mixed in the middle, while the Channel one sequence was slowly panned left to right and back again through the stereo field by a cycling Maths triangle function. The stereo output of X-Pan was sent to Mimeophon for some finishing with beautiful repeats and Halo.

Modules Used:

Tempi

René Mk2

Multimod

Maths

Spectraphon

QMMG

X-Pan

Mimeophon

Wogglebug

Outboard Gear Used:

Noisy Fruits Lab Lemon

Improvised and recorded in one take on iPad in AUM via the Expert Sleepers ES-9.